Wildlife collaring, which strategically puts data-collecting collars on animals that can then be tracked and monitored, allows scientists, conservationists, infrastructure planners, policymakers and other stakeholders to understand how a group of animals moves. This includes keeping track of habitat use, observing migration patterns over time, making behavioural observations, and monitoring population levels. This enables data-informed decisions when it comes to supporting wildlife corridors, building linear infrastructure, implementing conservation interventions, and more.

Alongside our partners, Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), Wildlife Research and Training Institute (WRTI) Kenya, Marwell Wildlife Conservation, Association of Zoos and Aquariums, and the Leiden Conservation Foundation, Grevy’s Zebra Trust conducted a collaring exercise in September 2023. This was conceived by KWS through the Grevy’s Zebra Technical Committee, which expressed the need to have more up-to-date information on the movement of wildlife around the LAPSSET areas of Northern Kenya. Some of the data that was being used to inform decision-making was from the early 2010s, so there was a sense that more current information was needed.

The strategy for conducting a collaring exercise is different for every type of animal, but for Grevy’s zebra, we chose to primarily collar adult females because of the way the herds are structured. They have what we call a fusion-fusion society, which means they mix and match and there are no permanent groups or families. They meet up for water and forage then split back up in whatever ways they feel like during that time. In general, the female Grevy’s tend to move more, with males exhibiting more territorial tendencies, especially as they get older. Although we prioritised female zebras in this exercise, we also planned on putting two of the total 22 collars on male Grevy’s in order to learn more about bachelor herds, which are made up of younger males.

Another factor that can make it challenging to collar a Grevy’s zebra is if it has rained recently. Any sort of rain will change everything, but not in a predictable way. Some move towards the rain, others move away from it, it’s impossible to know.

There are many moving pieces that go into collaring a Grevy’s zebra. In a vehicle, we would get near a herd and choose the animal we wanted to target. Then a small chase would ensue. From the moving vehicle, a doctor with a sedative dart gun would shoot the chosen animal and as soon as the Grevy’s zebra would start what we call high stepping (which means it’s getting a little bit woozy), everyone in the vehicle would jump out, grab the animal, and lay it on the ground. The Grevy’s zebra were not put fully to sleep but were simply sedated so that they were relaxed.

This process of catching the zebras can be straightforward or complex depending on a variety of factors, including the level and type of human interaction the animals are used to. While some are fairly familiar with tourists, for example, others are in more remote or conflict-prone areas. To help us categorise different herds, we came up with a reaction index to gauge the expected response of the Grevy’s based on their location. Grevy’s that were rated with a 1 are very docile, whereas those rated as a 5 were incredibly jittery and hard to catch.

The darting itself was quite an adventure because many of the veterinarians were used to Grevy’s in places like Lewa where they are fairly docile and the most extreme reaction you’re likely to get from them is that they’ll turn around and look at you. Shaba, however, where we started, they wouldn’t stop running away from us. The real excitement started in the El Barta region. Animals there were solidly 5 on the reaction index and forced the veterinarian in charge to attempt darting while driving approximately 120 kilometres an hour, which was a huge challenge.

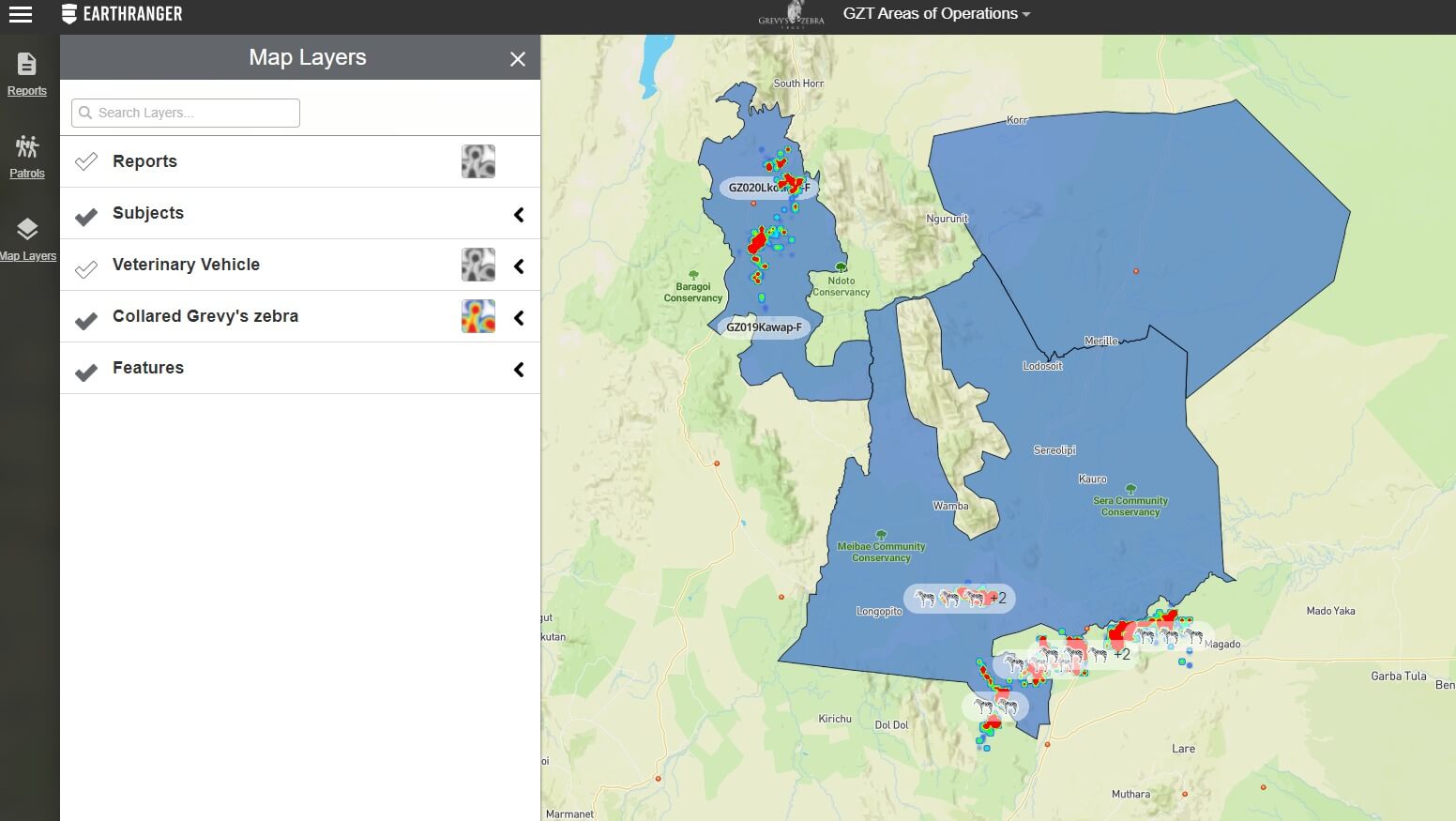

Heat map of 18 collared Grevy’s zebras’ movement from EarthRanger.

While the collar was being put in place, other measurements and samples would be taken. We targeted an ambitious amount of information, reaching a level that has never been done in the wild. Being this close to a Grevy’s zebra takes a lot of energy and resources, so we took the opportunity to learn as much as we could, getting as much data as possible as we secured the collar. We had people collecting samples for the lab, morphometrics measurements, and stripe ID photos, as well as the first weight measurements taken from wild zebras. We collected several different datasets from the Grevy’s zebra that we darted while they were sedated, but then we will also be able to get the collar data moving forward. We’re looking at a treasure trove of data from this activity. Once everything was finished, the doctor would inject the zebra with a reversal of the sedative and it would get up and run away.

Overall, the collaring experience was a great success. We were able to get 22 collars on different Grevy’s zebra. Looking ahead, we are eventually hoping that through modelling, we will be able to estimate the weight of a Grevy’s zebra just from body measurements that can be taken without having to go through the sedation process. For the collared zebras that are closer to places that we can monitor, we are interested in not only seeing where they go but also who they are associating with. This means we will be able to start to recognise if there are any patterns in how the different groupings form. We will use the information we collected during the exercise itself, plus the data we will continue to collect from the collars, to help us more effectively understand and protect these animals.