Thank you to Mollie Matthews, who provided this blog for us after her time in Kenya. She is a final-year Anthropology and English Literature student at Durham University. She is also a passionate conservationist looking to go into environmental management and conservation coordination.

When thinking of the sole organisation in the world which works to protect the endangered species of Grevy’s Zebra (Equus grevyi), I could not have imagined how far flung and diverse their efforts would be. It may be the only organisation with the goal to protect Grevy’s zebra, but its scope extends so much further than the protection of zebras. It took only one week at the Grevy’s Zebra Trust (GZT) field camp in the Samburu bush, to experience this realisation and become utterly blown away by the passion of the community and GZT staff in their efforts to conserve not only the Grevy’s Zebra, but the environment and sustainability of life.

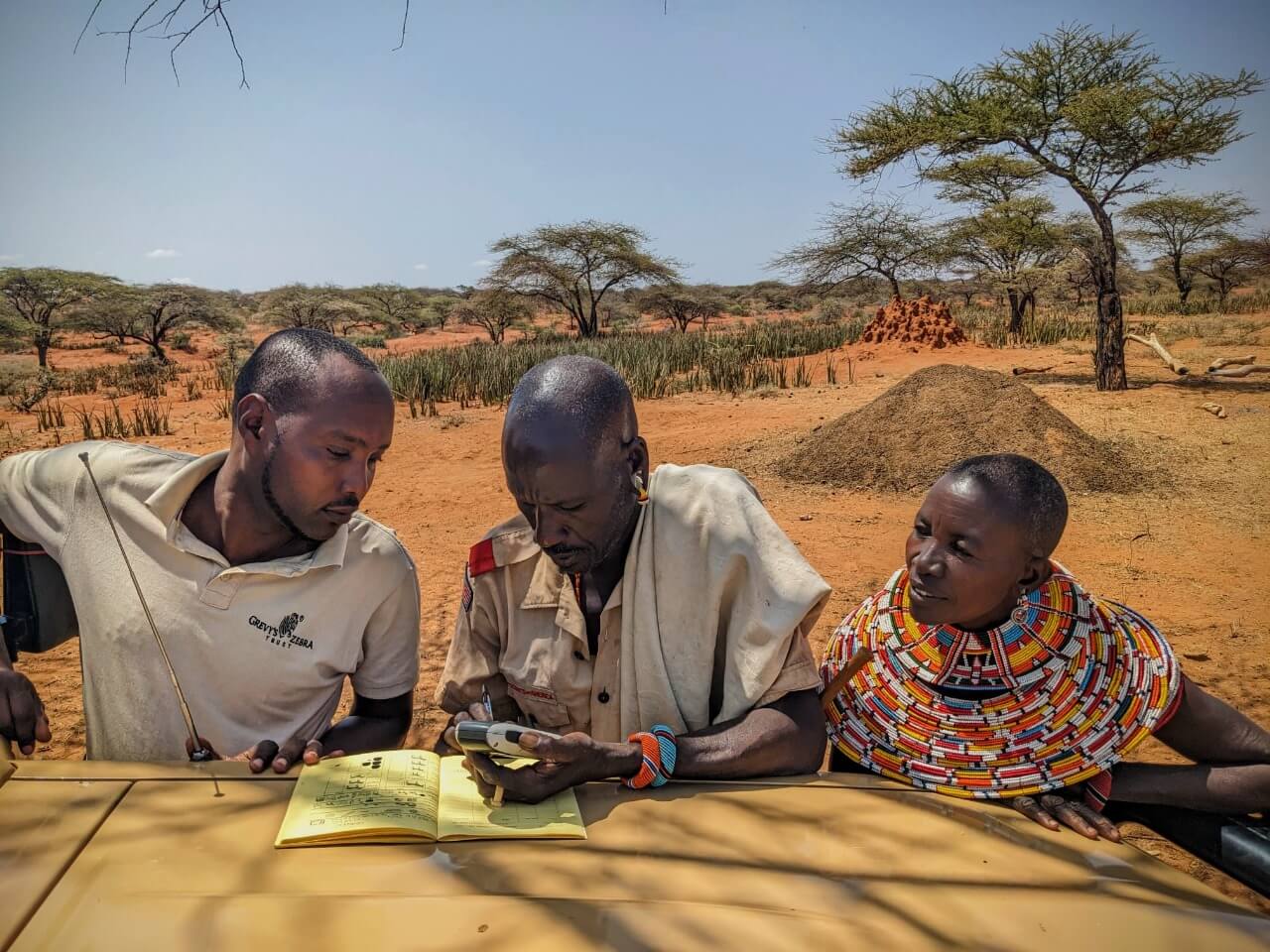

The collaboration between the community and GZT means that community knowledge and traditions are respected and upheld, alongside aid and education on sustainable land management for the most effective and efficient use patterns. The methods that the community are implicating include grazing block rotations, short term boma rotations for degraded land restoration, the creation of buffer zones and dedicated settlement areas, and water run off reduction. These projects are driven and delivered by the community which creates a vast amount of community authority and ownership over such solutions. Alongside GZT’s support, communities in Northern Kenya have begun to witness the benefits of regenerative grazing and healthy rangelands techniques; this has ultimately resulted in species recovery and livestock quality improvement. Through GZT’s partnership with communities, solutions to threats on humans and animals are being combatted with programmes centred on local values, interests and actions: an aspect which stood out to me in the pasture and rangeland management systems.

An example of this can be seen with ‘Nkirreten’ – a sanitary pad project run and managed by female community members – most of whom are single mothers, uneducated or previously unemployed. It is a project which not only enables women to work and enhances their rights and autonomy, but also stands as a symbol of hope, unity and empowerment for the women within their community. The project has led to the initiation of community women’s meetings where discussions of traditionally unspoken topics such as female hygiene, family planning, gender-based violence, female education and much more, have begun. The result of this is an increase in autonomy and respect for women – an understanding of their presence within communities. The women who I met no longer have to suffer in silence – they have a safe space for discussion and support – they now have choice.

The same home. The same environment. The same dependency on the survival of their environment which stands as their home. A sharp reflection of the keystone to the rangeland management and conservation movements that I witnessed – the lives of the people and the wildlife are inextricably linked. The need and potential for a symbiotic relationship is desperate. Yet the uplifting and blatant links between community and conservation are strong and effective. Through the creation of community conversations about conservation, there is a permeating hope for harmonious coexistence and the preservation of traditions alongside adaptations.